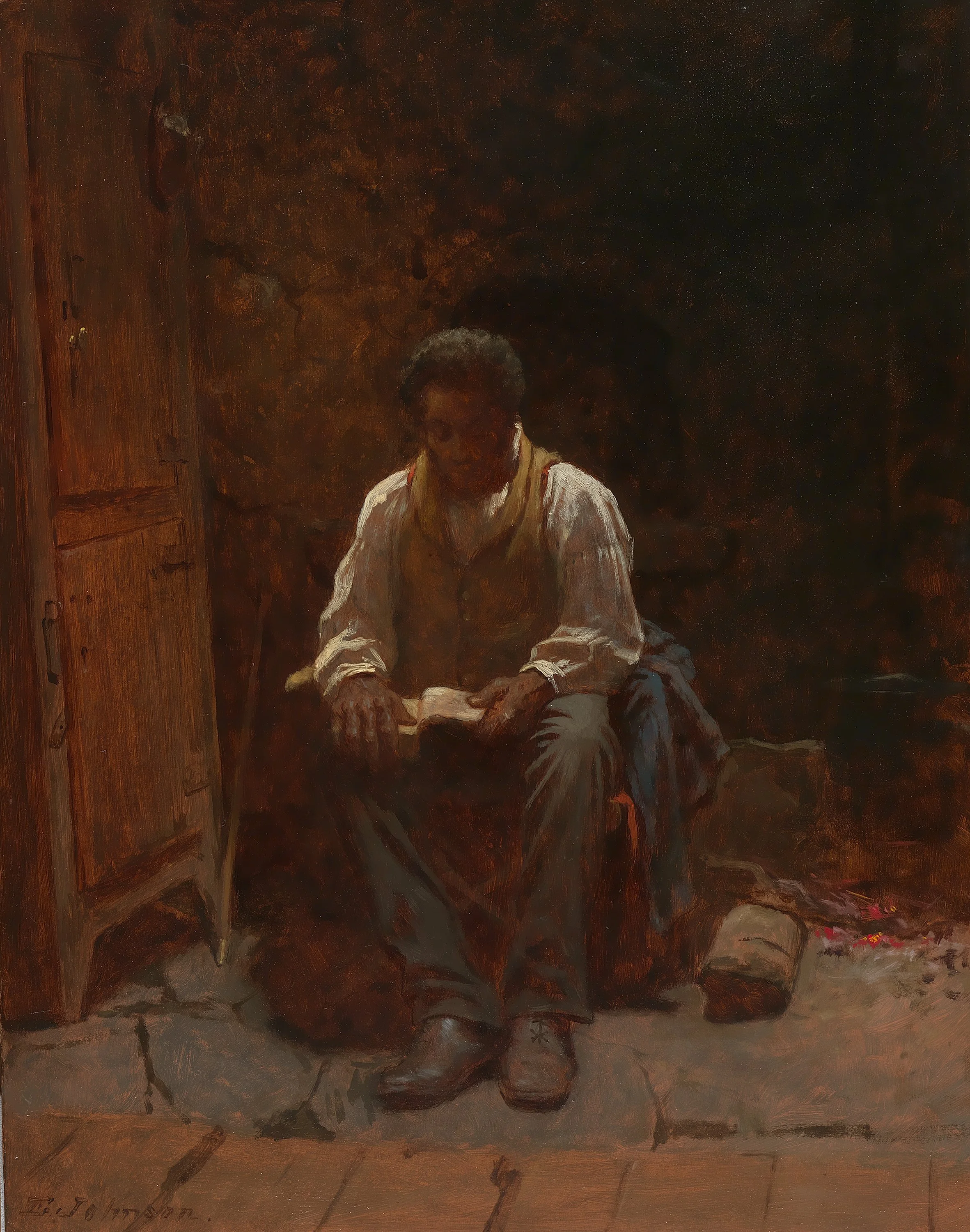

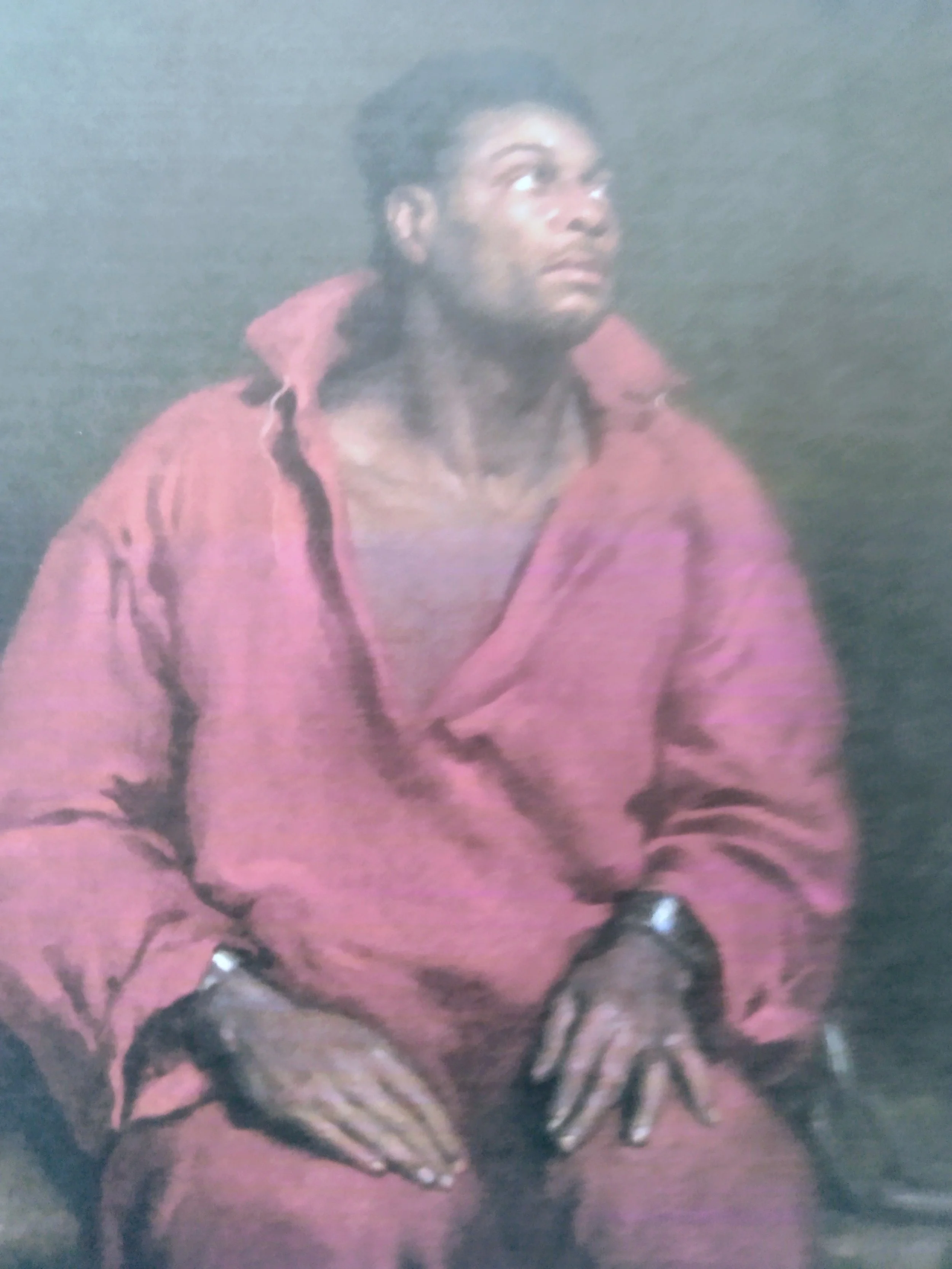

“The Lord is My Shepard” oil on canvas by Eastman Johnson Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

In this year that we begin the 250th commemoration of the American Revolution, we are continuing to look at this monumental event in new and nuanced ways; these last two generations especially, have sought to seek out those lesser-known heroes of the War of Independence, including patriots of color.

Stories of the heroism of patriots of color first emerged in newspapers during the course of the Revolutionary War. Those veterans who were well known in their widely dispersed communities were acknowledged as “soldiers of the revolution” in local newspapers upon their deaths, and many stories were later reprinted or retold in books during the rise of abolitionism, in the wake of the Civil War, and during earlier commemorations of the American Revolution.

The story I am retelling today is one of the earliest to be published in the twentieth century. It was printed in the “The Varnums of Dracut,” a biography written by John Marshall Varnum and published in Boston in 1907. As we will see, nearly all mention of enslavement in the family history highlights the well-known efforts of brothers James Mitchell Varnum and Joseph Bradley Varnum to end the practice of enslavement and prevent its growth into the emerging nation after the Revolutionary War.

While the abolition of slavery was a conviction the brothers shared with cousins and other family members, what was scarcely included in the family history was the early ownership of enslaved individuals within the Barnum households.

The first to be noted was an indigenous man named Toby, buried in the far end of the family plot when he died in 1744. It’s uncertain as to who among the Varnum’s was the enslaved Toby’s owner, but it could have been the Samuel, his brother Thomas who owned an enslaved boy named Jupiter,[i] or his son Joseph.

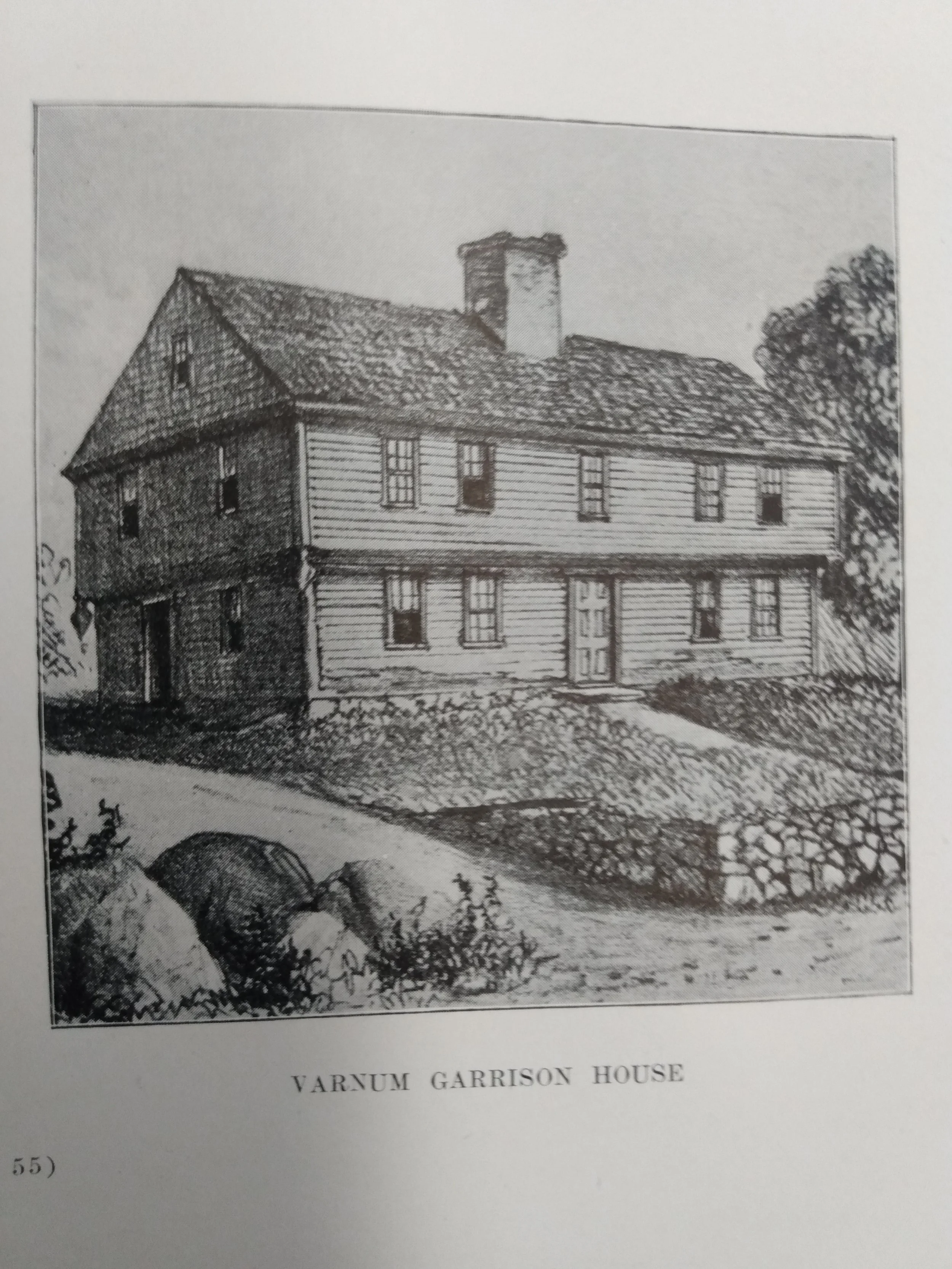

Illustration of the Varnum Garrison House, Dracut, Massachusetts

Joseph Varnum (1672-1749), the son of Samuel Varnum (1619-1705), purchased two enslaved children during his generation’s years at the family’s Garrison house. In 1728 Varnum purchased a nine-month-old boy who may have been born to an enslaved woman of nearby Billerica. Such a purchase was widely in favor among large landowners of New England during this period. The manageability of young boys or girls to raise and groom for domestic workers or laborers on their large estates brought a surge of young captives to the docks in Boston and Newport, Rhode Island as well.

He named the boy Cuff and brought the enslaved infant into his home to be raised as a domestic slave. It is this enslaved boy who is mentioned in the family history, and only in a footnote; an observation by the biographer that the young man had grown into a “shrewd and cunning fellow.” Varnum subsequently purchased a female child named Pegg to be a second domestic laborer. When his will was filed in 1746, Cuff is listed as a “Negro man servant” valued at L320 and Pegg, as a “Negro woman servant” valued at L230. On Joseph Varnum’s death three years later, they became his wife’s property.[ii] His son Samuel Varnum (1714-1798) would then have grown up in the household with the two enslaved individuals.

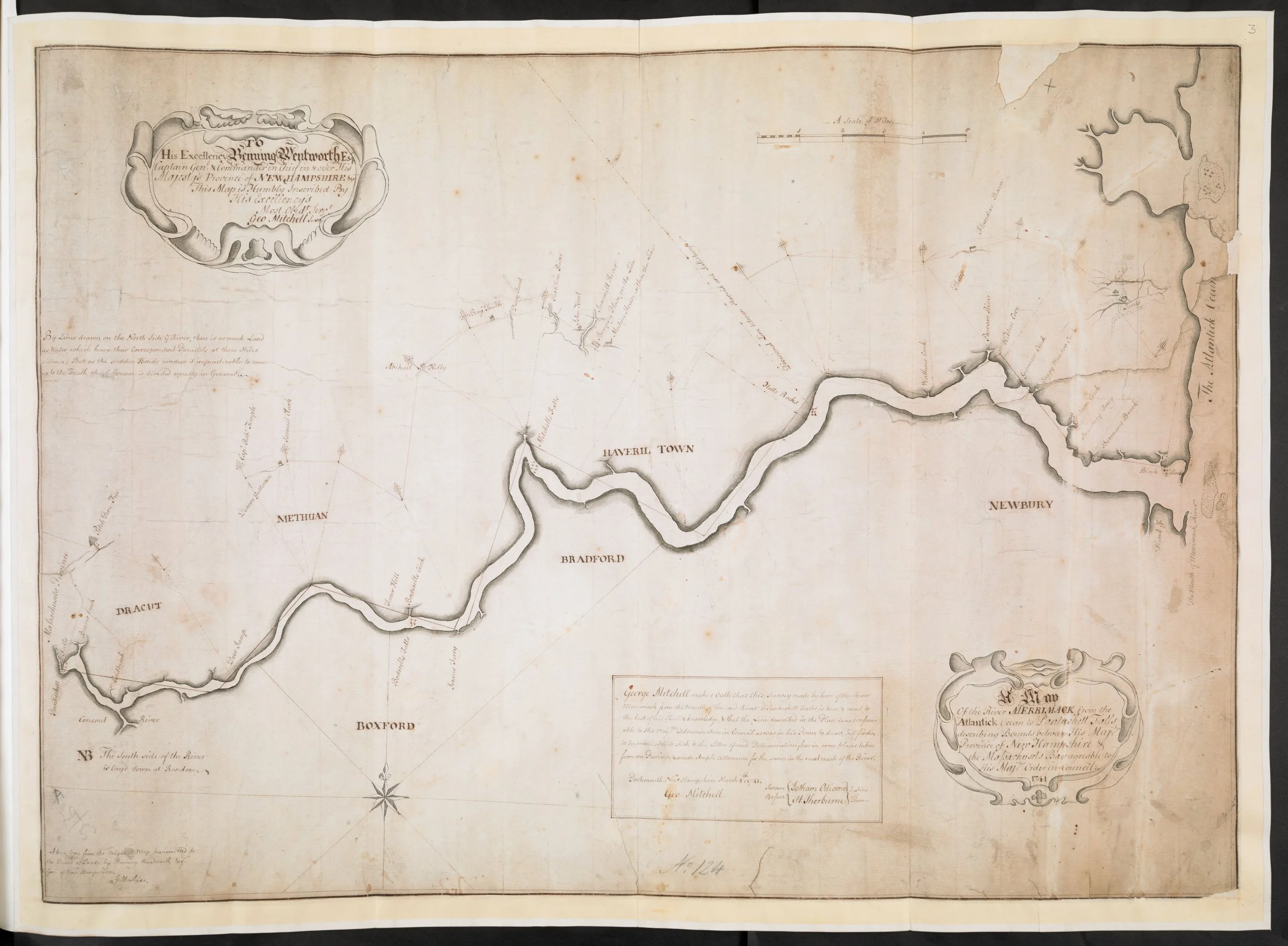

Illustration of the Merrimack River as it flows through the Commonwealth Cortesy of Wikipedia

As the Varnum’s were a farming family, their expanding numbers born into later generations continued to obtain land for their heirs, including the purchase made of some 700 acres “in the easterly part of Dracut” by Joseph Varnum from Samuel Prime in 1737. Varnum would later deed the land to his son Samuel, who would marry Prime’s daughter. An old description of the farmland notes that “It laid over two hundred rods along the river…It was somewhat fan shaped and reached northward over a mile to a point north of the nickel mine, including Belle Grove and the old Varnum Farms on the Methuen Road.”[iii]

Samuel Varnum Jr. (1715-1795) wed Mary Prime on January 4, 1737. Unfortunately, the bride was to live little more than six months into her marriage, dying June 8, 1737. Certainly, the unexpected death cast a pall over whatever plans Samuel had for the farm and a family of his own. It was likely his brother Joseph who coaxed him into another relationship. On October 26, 1738, Samuel was wed to Hannah Mitchell of Haverhill, Massachusetts; the sister of Major Joseph Varnum’s wife Abiah.[iv]

Samuel and Hannah settled on the land deeded from his father where he continued to live and farm throughout his lifetime. The couple suffered the not uncommon loss of their first three children, Mary, born January 1, 1740, James, born December 5, 1741, and Hannah, born November 1, 1744 in a wave of illness that swept through the community.[v] All three children perished between December 2, 1746 and January 7, 1747; James and Hannah dying within a week of each other into the new year.

Hannah Varnum was heavily pregnant at the time of her suffering the deaths of her children. On February 17, 1748, she gave birth to a son named Samuel. He would survive infancy, and the couple would have another son on December 17, 1748, whom they named James Mitchell Varnum, after Hannah’s father. A third son Joseph Bradley would be born little more than a year later on January 29, 1750. These three brothers would all live to adulthood, as would the remainder of the growing family. Samuel and Hannah would have six more children between 1753 and 1764, daughters Hannah, Mary, Abiah, and Abigail would be born before another son, Daniel, and the youngest daughter Martha completed the family.[vi]

During the early years of his marriage to Hannah, while establishing the farm deeded by his father, Samuel also purchased a pair of infant children born of an unknown enslaved woman at an auction in Boston. Their certificate listed the boy and girl’s surname as Royall, so we know that they were born on the large Royall estate in Mendon, Massachusetts.

Samuel Varnum started back to his farm in Dracut, but the female infant died in a horrific accident along the way. A story repeated in the family history is that the two infants were placed in saddlebags for the journey and the girl fell out as they rode, suffering fatal injuries. The boy would survive into adulthood and live into old age. Ryall, or Royall Varnum, as he was named, would become a singular part of the family history, and in particular, known for his relationships with brothers Joseph Bradley and James Mitchell Varnum.[vii]

Samuel Varnum’s intention in bringing two infants he would enslave into the household of his own young children remains unclear. As the infants would have needed constant attention, as well as feeding. It is likely that another enslaved woman of the family, or possibly a hired woman; was added to Varnum’s household for that purpose.

While his duties at the time were largely spent overseeing production on his farmlands, the education of the children was left to young mothers. By marrying the Mitchell sisters, Samuel and his brother had aligned their families with a prestigious and well-educated family of Haverhill. These ties would be of significance in the lives of their children as they grew into a colonial world of privilege and public service. Samuel Varnum in fact served the town in several capacities over the active years of his lifetime. He also, as was his father before him, an owner of enslaved children.

Image of Pawtucket Falls, Dracut, Massachusetts Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

Industry was a lesson more commonly imparted to children in this era. As Samuel Varnum and his brothers shared an interest in the grist and sawmills that Joseph Varnum had established at Pawtucket Falls, whose power was gathered by a wing dam that siphoned the current to the waterwheel. As the Varnum brothers continued the running of the mills into the mid-18th century,

The heavy work of felling and hauling timber was likely performed by a seasonal population that hired themselves out for all manner of farm labor.[viii]At the mill however, the equally hard work of lugging sacks of grain and flour, unclogging the bolting machine, and sweeping the mill may well have been performed by enslaved individuals within the family, perhaps Silas Royall and others, or through the hiring of free blacks from the small, but resilient African-American community in Dracut, Massachusetts.

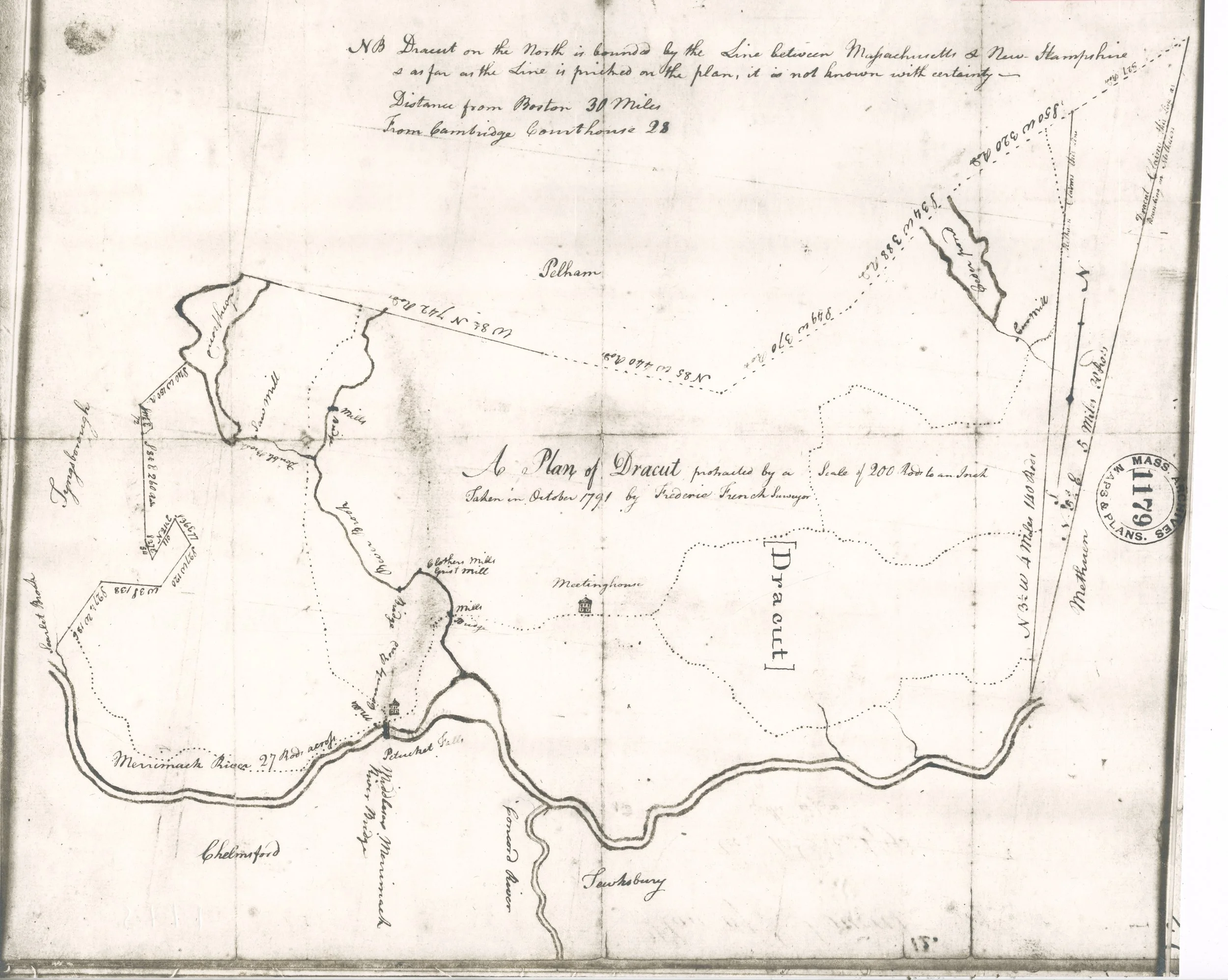

Map of Dracut, Massachusetts 1791 Courtesy of the Dracut Historical Society

The town was inhabited by a number of free black families. Among the first of the free black Americans in Dracut was Antony, or Antony Negro, as he was registered. A former enslaved man from Concord who had emigrated with his new wife to the town in 1706, he was given just the 12th land grant issued by the town, that gifted him several tracts of land around Cedar Pond, 28 acres on Marsh Hill, and 66 acres east of Beaver Brook in what is now Pelham, New Hampshire.[ix]

After the untimely death of his first wife in 1712, Antony Negro was married again to a woman named Sarah (Sary) MIngoe. The couple would raise nine children, Joseph, Margaret, Robert, Hannah, Sarah, David, Jonathan, Peter, and John. Indications are that Antony was a dairy farmer for most of his years in the town.

Upon Antony’s death in 1740, his probate inventory shows that he owned ninety acres of land in Dracut. Some of the lands were sold, and his will divided up the estate among all his children but John, who may have died young.

For many years the area of East Dracut, with its close proximity to the black community in Pelham, New Hampshire, was called the “Black North”. Tony’s Brook which runs through the region was reputedly named for Antony Negro, and “Peter’s Pond” and the surrounding area named for his son.

The naming of the region seems to indicate a willful separation from the black community. Indeed, the members of the Congregationalist meeting house voted in 1748 to bar blacks from sitting in pews during services. Yet by the time of the young James Mitchell Varnum’s upbringing, a shift seems to have occurred.

The Freeman and Hartwell families lived in town, and the Lew family were well known in Dracut, the patriarch Barzillai Lew being a musician of some fame, who purchased Dinah Bowman in 1767, married her, and raised a large family who were also trained as musicians.[x]

Lew had served as a member of the English forces in the 1760 Indian War, and later in his middle age as a fifer during the Revolutionary War. He was in service at Bunker Hill. When he returned to Dracut he enlisted with the local militia along with younger patriots of color from the town.[xi] He is listed as the fifer on the muster roll of Captain Joseph Bradley Varnum’s company of Dracut volunteers who reinforced the northern Army in September 1777.[xii]

This generation then, of the Varnum brothers, as with the sons and daughters of other New England families began to see those people of color about them in a different light from what their forefathers had allowed themselves. Certainly, this change was also influenced by early pre-abolitionist activists in the colonies. The fervent newspaper readers of New England would have consumed the stories of Quaker Benjamin Lay’s antics in meeting houses and in the streets of the various communities he and his wife inhabited. The wave of new light ministers and the popularity of outdoor evangelical meetings suddenly equalized the attendees, both physically in presence, and spiritually. As a result, ministers like Ezra Stiles, began having prayer meetings, albeit separate in a private home, for those worshipers among the black population of Newport, Rhode Island.

Varnum and his siblings, along with other young American men and women who would form and shape the new nation after the Revolutionary War would grapple with the moral questions raised by continued enslavement, incited by an enlightened declaration of all Americans being equal, and having the right to liberty, freedom, and the pursuit of happiness.

With the word of shots fired in Concord and Lexington on 19 April 1775, Col. James Mitchell Varnum marched the Kentish Guard from East Greenwich to Providence, and then Pawtucket where they were informed that the British had withdrawn to Boston. His brother Joseph Bradley Varnum marched with the Dracut militia under Captain Stephen Russell.

On May 8, 1775, Nathanael Greene Jr. received word from Secretary Henry Ward that the General Assembly had named him Brigadier General.

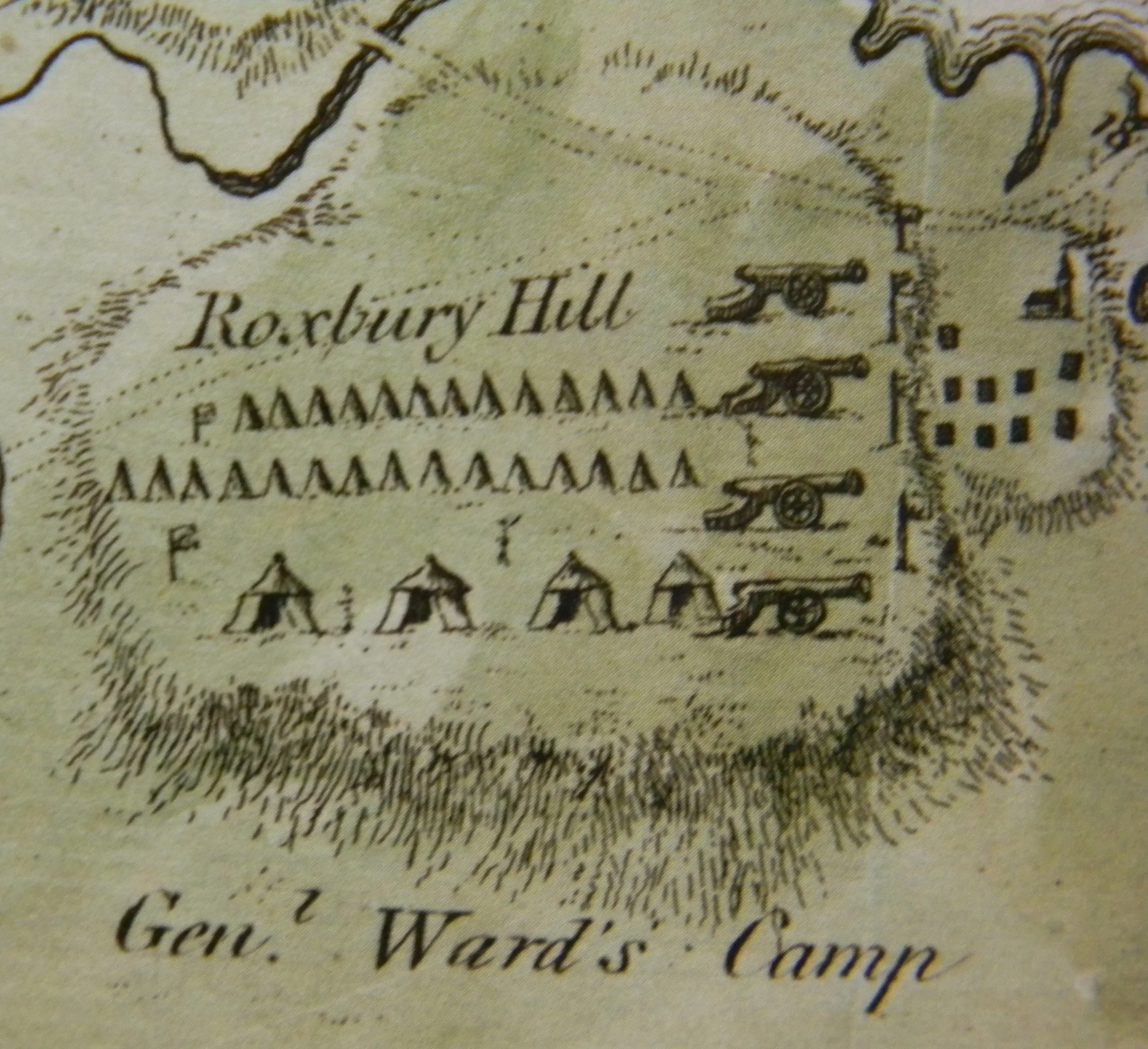

Detail from map of the Siege of Boston Courtesy of the Rhode Island Archives

With their arrival, Varnum’s brigade was taken into the Continental Army and renamed the 12th Continental Regiment. The regiment contained ten musket companies of sixty men each company, with an additional ten officers overseeing them.

The first incident in which Rhode Islanders engaged in combat came upon the afternoon of June 17th when one hundred men were dispatched under command of 2nd Lieutenant Christopher Greene to be part of General Israel Putnam’s line of defense along an entrenchment at Breed’s (more commonly called Bunker Hill); said to hold a force of three hundred men.

Men from Dracut, Massachusetts including two of James Mitchell Varnum’s brothers, and several cousins were also engaged in the battle. John Varnum Jr. of Capt. Peter Coburn’s Company fought in the battle, as did three nephews. A distant cousin from New Hampshire was wounded in the conflict.

The Rhode Island regiments, other independent companies, militia, and riflemen from the colonies occupied Prospect and Winter Hills that summer.

While the majority of officers were from elite, or at least from what we describe as middle class white families, the soldiers themselves were an amalgamation of backgrounds and races. While the traditional histories of young New England farm boys throwing down the plow and picking up a musket were certainly part of the population, immigrants, Indigenous, and Black Americans had served in the region’s militia throughout the tumultuous 18th century in North America; and they continued to do so as companies marched and joined the Siege of Boston. Of the assembled 2400 members of militia gathered there, an estimated 120 were soldiers of color.[xiv]

In Varnum’s Continentals that summer were a handful of these patriots of color. Among them were London (or Louden) Thompson, Jehu Pomp, Edward Anthony, and Jesse Willis. A former worker at Brigadeer General Nathanael Greene’s forge named Jonathan Greene, was also present. Regiments from Connecticut and Massachusetts also held significant numbers of black soldiers. Among those from Dracut, Massachusetts who served were Anthony Clark, Smith Coburn, Chester Parker, and the Varnum family servant Silas Royal who marched with a company from Dracut that included some of Varum’s nephews and cousins.

On January 1, 1776, the Continental Army was reorganized with the previous three Rhode Island Regiments reduced to Varnum’s Regiment, now renamed the 9th Continental Regiment, and the 11h Continental Regiment, now under command of Col. Daniel Hitchcock.[xv] These companies were brigaded with two from Massachusetts, Little’s 12th Continental Regiment, and Hand’s 25th; to form the new brigade under Brigadier General Nathanael Greene.

Returning to the field, Varnum brought with him members of his family. His brother Samuel Varnum Jr. enlisted in the 9th Continentals. Silas Royal[xvi], was also among the newly enlisted men of the regiment.

Painting of the U.S.S. Hancock, a privateer which accompanied the U.S.S. Franklin

As a free black man, Silas Royal had first enlisted in Massachusetts and already shown himself as a patriot of color. Royal had signed aboard the privateer U.S.S. Franklin under Marblehead captain John Selman. Originally a fishing vessel, she was fitted out with six cannons in 1775 and enlisted under Washington’s orders as part of the fleet under Commodore John Manley which sailed out of Salem in 1775 as part of the fledgling American Navy’s first expedition to disrupt the shipping of weapons to New York from Nova Scotia.

In October 1775, the Franklin, along with another ship, the Hancock, were ordered to intercept two brigs heading up the St. Lawrence River. The two American schooners, rather than engage with the British vessels there, sought easier quarry off the coast of Cape Canto, where they captured five vessels or “prizes” of dubious origin. The crew also conducted a raid on the Canadian settlement of Charlottetown. This illegal action caused the dismissal of both commanders. Silas had earned 30 pounds in wages for his time aboard.

By December of that year, he was listed as Silas Royal and serving in Captain Jonas Richardson’s company of Colonel James Frye’s 10th Massachusetts regiment. He was given an order to receive a “bounty coat or its equivalent in money” on December 22nd.[xvii]

In January, he enlisted in Capt. Jacob Reed’s company of Varnum’s 9th Continental Regiment. In the family biography, “Ryall” as the family called him, is mentioned as “accompanying Varnum on all his military expeditions.” Records show that as a private, he was discharged from duty April 1, 1776.[xviii]

Illustration of Salem harbor in the Colonial period Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

After his discharge he returned to the life of a privateer. Silas Royal served aboard the sloop Revenge, a privateer commandeered by Captain Joseph White, a Salem merchant and slave trader. While Royal’s pay and prizes came to 146 pounds, 1 shilling, he received only four pounds, the remainder being pocketed by one Joshua Wyman, who claimed his services.[xix]

Wyman’s claim would mean years of uncertainty for Silas Royal. With advice from James Mitchell Varnum, Royal had writs drawn against Wyman on April 30, 1777, at the Middlesex Court of Common Pleas.

Image of the Salem, Massachusetts Courthouse of that period. Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

The Hearing on the case was held in September, and documents made public Wyman’s claim that he had purchased Silas Royall from Samuel Varnum in 1767 for work on his farm in Woburn, Massachusetts. The claim also seems to imply that Royall had enlisted without his consent in 1775 but met up with him in Boston after his enlistment in Varnum’s brigade and persuaded him to return to Woburn in exchange for his freedom. When Royal signed aboard the Revenge, he was allegedly still owned by Wyman.

The Court rejected this argument and ruled in Silas Royal’s favor, partly based upon such evidence as presented in petitions sent by James Mitchell Varnum and other family members, but also by one Edward Gibaut, an “agent for the armed sloop Revenge,” which

“…made a Cruize in the year 1776 and took several prizes. That one Silas Royall was a hand on board Said Sloop and his share of the Prize money amounted to one hundred & forty-Six Pounds, one Shilling & Seven Pence half penny, four pounds of which I paid to Said Silas, the Residue to one Joshua Wyman on his Account, the Said Wyman told me the Said Silas was his Slave and shewed me a bill of Paper which he Said was a Bill of Sale of him.”[xx]

Wyman’s attorney filed an appeal to the court’s ruling, essentially the first of many tactics the defendant would use over the years, before Royal ever saw a pound from the ruling.

With his privateering days over, and the majority of the male members of the family engaged in the war, Silas Royal had been called back to Dracut and oversaw the management of Joseph Bradley Varnum’s farm and likely helped out with other family farms that proved to be quite profitable during the war.

An illustration of the kidnapping of an enslaved individual. Courtesy of wikipedia Commons

In June 1778, James Mitchell Varnum received word that Royal, had been sold into enslavement by Joshua Wyman, the same man who had claimed him the year before. Varnum’s nephew John, recorded the entire story in his diary, much of which was reprinted in the family genealogy:

“…ye news was brought from Westford by Joseph Varnum Jr., and that said Ryal was carried off in a covered waggon Handcuffed. On hearing of which I immediately called for my horse, Galloped to Jos. Varnum’s company to know the Certainty.”[xxi]

Once confirmed, the Varnum’s set out “with orders to pursue with all possible speed, overtake, Bring back, and not suffer with such arbitrary voyalance to Escape with Impunity.”

Silas Royal had been purchased by a well-known trader named John White, as the journal describes him, “the Scurrulous Tinker of Haverhill, that Bought him (at ye same time knowing sd Ryal was a freeman) sd White had imprisoned him.”

White claimed to authorities that Ryall had taken his pay from the Continental Army and deserted. Moreover, that he had “stolen from sundry persons & was a thief…”[xxii]

John White was indeed a well-known man in Haverhill. His family had called the village home for three generations, many whose sons had gone to sea. White lived in his four-story clapboard, flat-roofed mansion house, surrounded by gardens leading down to the riverside. He also owned a large brick tavern in town that was one of sixteen buildings lost in a disastrous fire on April 16, 1775. Other buildings lost to the flames included a rum distillery, several residences, and the merchant warehouses of Joseph Duncan and James Dodge. It is little surprise then, that White now resorted to engaging in the nefarious attempt to brand the man he hated a criminal, and to sell Silas Royal.

“Enslavement” Oil on canvas by A.C. Simpson Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

Joseph and Jonas Varnum rode to Boston to complain to General Heath, “had sd Ryal released & a promise that he would take Notice of said White.” The men confronted John White as well, who claimed ignorance in knowing Ryall was a free black man. The Varnum’s told White that he knew the charges he had filed against Ryal were not true. They took him to task for his treatment of the family servant, and told White they had complained to General Heath and had obtained Ryal’s freedom,

“He was Extremely angry, Curst & Wore Profainly…. He said that all such Damd Negroes aught to be Slaves…”

According to the family history, the brothers

“told him that Ryal was as Good a man & of as much honour as He…that they could not forget his conduct upon Ryal, and that they, on sd Ryal’s Behalfe, should bring an Action of Damage for false Imprisonment, that such arbitrary Tyrants & man stealers should not go unpunished.”

The brothers had uncovered a detailed plot between Wyman and White, where the provisioner, as we’ve seen, would claim he had purchased Silas Royall from Samuel Varnum in 1767, and displeased as he was with Royall’s attempt to obtain his wages; was free to sell him to White, whom he urged to sell at a high price to a slave captain taking cargo to Barbados, “so that he might never be heard from again”.

James Mitchell Varnum would counsel Silas Royal, and file suit on his behalf against Wyman the following year, just one duty that he was to attend to as his military service in the Continental Army came to a close.

Settling in town also allowed him to set up office as an Attorney once again, he was soon handling the Greene’s legal affairs and taking on local cases. Though duty pressed him to remain in the state, he counselled Silas Royal on his impending case against Joshua Wyman and John White for the kidnapping and attempted sale of the free black man. A hand-written list sent to Silas Royall, instructed him, and what counsel he could obtain, to prepare for the case in the following manner:

“1. Take a deposition to prove the bill of sale made to White

2. Take a deposition to prove that Wyman has confessed to making such a bill of sale, that he was sorry for what he had done.

3. Make deposition to prove your confinement in irons &c., that Wyman was knowing to it, and that White intended carrying you to South Carolina as a slave.

4. Find out, if possible, who were witnesses to the bill of sale, and take their depositions.

5. Take deposition to prove yt Wyman intermeddled in the affair of your release and endeavored to have those prosecuted who released you. Let the witnesses ascertain, as near as they can, the date of the bill of sale.

6. Get a copy of ye whole case at ye Superior Court when your Freedom was declared.

P.S. Desire ye Justices of Peace to be particular in their captions, viz:

A Plea of Trespass whereas Silas Royal is Pt. [Plaintiff] and Joshua Wyman Deft. [Defendant]. Depending before ye Superior Court at Taunton, in October A.D. 1779

N.B. Follow your instructions exactly without minding other people’s nonsense.

The list or letter itself is a remarkable document, instructing a former enslaved servant in the legal practice needed to obtain justice, and believing full well in the capabilities of that man to follow his instructions and prepare the case set before the court.

Varnum further provided testimony that

“sd Royal inlisted into the Continental service in January 1776 & joined his Regt. at Prospect Hill, & did duty there as a soldier in Capt. Reed’s Co. and Col. Varnum’s Regt., and until the Regiment was ordered to march southward the 1st of April following, where the sd Wyman appeared & made a verbal promise to Royal as he had a bill of sale of him that if he would return home, he would deliver up sd bill of sale & that he would give him his freedom & 100 acres of land. Thereupon Royal was released from service and afterwards joined a privateer.”[xxiii]

A second Case would be brought against Joshua Wyman and John White, filed in the Bristol County Court of Common Pleas in September 1779, listing the plaintiff as ‘Silas Royal of Providence, Rhode Island,” and his attorney as James Mitchell Varnum, of Providence with William Bradford of Rehoboth. This would seem to indicate that Silas Royal was living with James Mitchell and Martha Varnum in East Greenwich at least during the time of these proceedings. While originally scheduled to be heard in October 1779, the case was not presented until October 1780 when Bradford and Varnum appeared on Royal’s behalf.[xxiv]

The Writ, as endorsed by Bradford stated the plaintiff’s complaint, that he had been

“Taken by Wyman from Woburn to Taunton on 3 June 1778 and held for ten days.”

Depositions from Joseph Bradley and Jonas Varnum detailed that “some time in the month of June 1778…they heard from [a] Person of Veracity…that Silas was seen being taken away in a wagon “with Irons on his hands, between Cambridge and Waltham…Crying for help.” The men supposed that White’s intent was to take Silas southward, as

“Many attempts of that sort, had Just Proseding that Time ben Made Against A number of Free Men & Women of his Colour.”

Indeed, in the January 1778 census of those able-bodied males in Dracut, only four men of color remained.[xxv]

Silas Royal sought the sum of $5000 in damages, but was awarded only one dollat, despite a damning deposition published by John White against Wyman:

Silas Royal would file an appeal but lose that appeal the following year.

The episode made Royal aware, that protected by the Varnum’s though he might be, of how fragile freedom was for himself and other free black men during this time of turmoil. Patriots of Color throughout New England joined militia, and eventually, as we’ve seen, the Continental Army. Rhode Island had passed a bill making any black or indigenous enslaved enlistee “absolutely free”. Other states followed suit or allowed owners of enslaved men to send one in his, or another family member’s stead. That is, to serve in their place.

Modern portrayal of a Revolutionary War soldier of color with comrades.

Many patriots of color served with distinction from these states. Others deserted the Army, and joined the wayward migration of those seeking work, or signed on a vessel for a time in the mariner trade, an always risky occupation, made worse in time of war.

On land was little better. Free blacks when venturing beyond the town in which they were known were always under suspicion. A scheme such as the one concocted to kidnap Silas Royall could easily be carried out in an era of such turmoil.

Even in the wake of the war, when a tide of emancipation swept south from Vermont into other New England states, the distemper of racism would not fully be erased. A journal entry of a town meeting in Dracut in April 1780 relating to a black woman claimed as an enslaved person reveals that such ideals of freedom for all, were not shared by every citizen:

“A Negro wench named Happis came here from Colo:… to advise relating to her freedom. She being 26 years old, advised she was free, that a land of freedom knows no slavery, that all attempts to keep up that practice (which hath been too long tolerated) are arbitrary, cruel and wicked, and Contrary to ye Laws of God and Christianity. And all that are assisting are abettors in robbing fellow Creatures of their liberty wherein God hath made them free.”[xxviii]

One Thomas Rugg, employed by Samuel Johnson of Andover who claimed the woman, attempted to take her by force from the meeting, “but was by her repulsed, and went off disappointed and ashamed.”

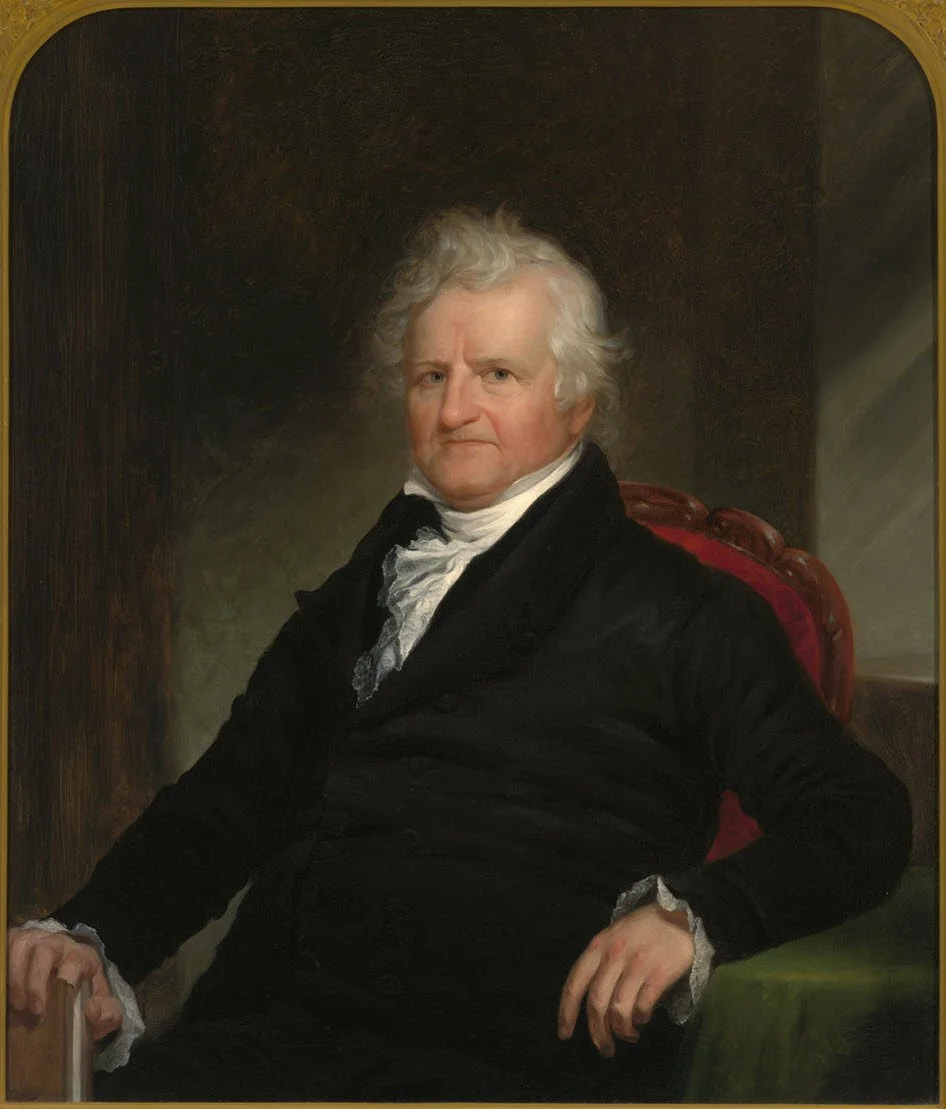

Portrait of Joseph Bradley Varnum Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

Silas Royal returned to Dracut and continued to help manage the farm of Joseph Bradley Varnum. He was also provided some land to occupy. In the family biography, Silas is said to have been immensely proud of his relationship with the brothers James Mitchell, and Joseph Bradley Varnum, and the role that he himself had played during the American Revolution.

The family history tells us that in his will, James Mitchell Varnum left funds so that Silas “be comfortably supported through life and honorably buried after death, at the expense of my estate…” The will in fact, was drawn by Joseph Bradley Varnum and is listed in the records of the Middlesex Probate Court, 22 May 1818. But the impact that this infant born into enslavement would have on this generation of a New England family, and on these two brothers of military and political influence is notable.

While Silas Royal, like many other patriots of color returned to their villages and towns as free men, they also returned to the grim reality that their service, while gaining a measure of respect in their communities, did little to raise their status above a hand to mouth existence and a remaining lifetime of poverty and hardship. While it is evident that Silas Royall helped to manage the farm for some period of time after the war, the will of James Bradley Varnum reveals that Silas Royal had been dependent upon him for some time when he named him a beneficiary.

Illustration from an Abolition pamphlet. 1792 Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

On his death in May 1826, Silas Royal was buried in the Varnum family plot beside the familiar grave of the indigenous man who had been a family servant. The distance from the family’s plot of closely grouped, elegantly carved gravestones and the plainly marked graves of their deceased servants is yet another reminder that no matter how genuine and well-intentioned the effort of 18th and 19th century families to emancipate and improve the lives of their formerly enslaved workers; that they had once been enslaved remained an unbroken boundary throughout their lives as free men and women; even unto the great equalizer death.

[i] Fitzimons, Gregory Gray Hawk Valley Farm Lowell Parks and Conservation Trust, 2014

[ii] Ibid.

[iii]Coburn, Silas R. History of Dracut, p. 111

[iv] Ibid. p. 128 Both sisters were the daughters of Capt. James and Martha (Bradley) Mitchell of Haverhill.

[v] Possible an early outbreak of “yellow fever” that had spread from Albany and it’s environs through it was believed, areas of New England. A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases Historical Society of Massachusetts, Vol. 1, p. 239

[vi] The Varnums of Dracut pp. 128-129

[vii] His birth name, as listed on the purchase was Silas Royall. It is likely that he and his sister were offspring of an unknown enslaved woman of the large Royall plantation in Dedham, Massachusetts. They would have been brought to auction in Boston within weeks of their birth.

[viii] Hawk Valley Farm, pp. 23-24.

[ix] Duda, Rebecca Peter’s Pond a little-known piece of Dracut’s Black History, The Lowell Sun, March 6, 2024

https://www.lowellsun.com/2024/03/06/duda-peters-pond-a-little-known-piece-of-dracuts-black-history/

[x] Slavery in Groton until 1780, The Groton Herald June 20, 2013

https://www.grotonherald.com/features/slavery-groton-until-1780

[xi] Lowell History: African Americans in Lowell University of Massachusetts Library, Lowell see

https://libguides.uml.edu/c.php?g=520711

[xii] Varnum, John Marshall, The Varnums of Dracut p. 192

[xiii] Ibid. p. 80

[xiv] Greenwalt, Phillip George Washington’s Integrated Army: The American Armies of the Revolution American Battlefield Trust, January 4, 2021, updated October 26, 2023 see http://battlefields.org/learn/articles

[xv] Despite poor health, Colonel Daniel Hitchcock had led militia and the Continental units from 1775. Many who served under him, including Lieutenant Colonel Ezekial Cornell, and Major Israel Angell, would become familiar names to Rhode Islanders through the course of the war.

[xvi] The certificate of sale given to Samuel Varnum lists the boy’s name as Silas Ryal. While the Varnum’s named him “Ryal” or Royall, that may be an indication that he and his sister were born of an enslaved woman of the Royall household of Medford, who held a large population and could likely have sent a pair of infants for auction at Boston.

[xvii] Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors in the Revolutionary War, 1775-1801 p, 12703, see

https://www.fold3.com/image/720198696?rec=685489901

[xviii] Ibid. p. 12702

[xix] Silas Royal, with counsel from the Varnum family, sued Joshua Wyman in September 1777 and received judgement for the full amount. It was not received by the court for another two years.

[xx] Research Summaries of Massachusetts Freedom Cases

[xxi] Ibid., p. 219

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Varnum, The Varnum’s of Dracut p. 222

[xxiv] Research Summaries of Massachusetts Freedom Cases p. 123

[xxv] Journal of James Varnum, February 1778, as printed in The Varnum’s of Dracut, p. 58

[xxvi] Quintal, George Patriots of Color National Park Service 2004

[xxvii] See: https://www.google.com/search?q=john+white+of+haverhill+in+court+1778&client=safari&sca_esv=04268fcd01117b60&channel=mac_bm&sxsrf=AHTn8zoKr4owEvb-XE0DxfiKXyxvPx15gA%3A1748019839747&ei=f6owaKisLZPS5NoPvK_HuA0&ved=0ahUKEwjo5-6sibqNAxUTKVkFHbzXEdcQ4dUDCBA&uact=5&oq=john+white+of+haverhill+in+court+1778&gs_lp=Egxnd3Mtd2l6LXNlcnAiJWpvaG4gd2hpdGUgb2YgaGF2ZXJoaWxsIGluIGNvdXJ0IDE3NzgyBRAhGKABMgUQIRigATIFECEYoAEyBRAhGKABMgUQIRigAUicL1DXC1jDKHACeACQAQCYAXmgAfAEqgEDMS41uAEDyAEA-AEBmAIHoALnBMICCBAAGLADGO8FwgILEAAYgAQYsAMYogTCAgQQIxgnwgIFEAAY7wWYAwCIBgGQBgSSBwMyLjWgB58bsgcDMC41uAfaBA&sclient=gws-wiz-serp

[xxviii] Varnum, The Varnum’s of Dracutt pp. 62-63.